The inky black, minty, unpleasantly bitter yet strangely popular Fernet Branca is at the challenging end of the amaro spectrum. That’s why I’ve been saving this recipe for last, having already had a go at my first damson amaro (popular, clear and bracing, quite bitter), a second damson amaro in the style of Amaro Montenegro, a third more balanced damson amaro, but losing some of the strength of character, and then the fourth damson amaro, alpine-style and the best yet. Spoiler alert: the damson fernet isn’t black, it isn’t as much as the Branca (which means it is nicer to drink!), but it definitely packs a punch and it works well as a recipe.

If you’re less interested in the history and explanations, jump straight to the recipe.

The origins of Fernet

Born in 1802, Bernardino Branca was by all accounts a self-taught herbalist and entrepreneur. He created the original Fernet recipe in Milan in 1845. Milan in the 1800s saw the start of other bitter liqueurs: Ausano Ramazzotti started selling his Ramazzotti amaro as an apothecary in 1815 (still successful to this day, although now owned by the French multinational Pernod Ricard), and by 1860 Gaspare Campari had created the initial Campari liqueur, within walking distance of the Branca family.

The history of Fernet Branca is an intriguing mixture of mythology and genuine evidence. For instance, it is likely that “fernet” was a trade term for a bitter medicinal preparation, coming from Germanic medical terminology, rather than the more fanciful tale of a “Dr. Fernet” as has been suggested. At the time, Milan was under Hapsburg rule as part of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia , and pharmacists were often trained in Vienna. So Bernardino initially sold his drink as a Fernet, and then re-branded to Fernet-Branca with his family name.

Museo Nazionale Collezione Salce, Treviso.

Branca’s vision was for a medicinal tonic, helping with digestion. Hence the aggressive bitterness and metholated taste: an uncompromising stance, uninterested in easygoing popularity (providing a good contrast to the history of Aperol I described a few months back). The company backed this with what was unusual branding at the time for a drink. In 1895 Leopoldo Metlicovitz (a pioneer of Italian advertising and poster design) created an authoritative, angry eagle clutching a bottle of Fernet, with the drink’s international reach shown by a globe. It was registered as a trademark and amazingly persists almost unchanged to this day. Not the logo for a light-hearted drink!

That sense of authority wasn’t just visual; Fernet-Branca is still a tightly controlled family business. The original founder Bernardino ran things together with his sons (hence the name “Fratelli Branca Distillerie” – the fratelli (brothers) were Bernardino’s sons). He passed the reins to his son Stefano after his death in 1882. Stefano himself died only 9 years later, and his widow Maria Branca Scala took over, running business operations and managing international expansion, taking a much more powerful role than common for women at the time. Eventually in 1907 Stefano and Maria’s son Dino took over. Dino was made a count (Conte di Romanico) by Vittorio Emanuele III, King of Italy, in 1938, cementing Fernet-Branca’s position as a pillar of Italian export and industry. Today the company is run by Niccolò Branca, Dino’s grandson.

By the turn of the century, Fernet was moving beyond its role as an after-dinner cure. Over in London, Ada “Coley” Coleman had been promoted to head bartender at the Savoy Hotel’s American Bar, reportedly serving the likes of Mark Twain, Marlene Dietrich and the Prince of Wales. She was one of the most influential mixologists of the early 20th century. And she’s credited with one of the first cocktails featuring Fernet, created for actor Sir Charles Hawtrey. “Coley, I am tired. Give me something with a bit of punch in it.” Coleman recalled him saying. “The next time he came in, I told him I had a new drink for him. He sipped it, and, draining the glass, he said ‘By Jove! This is the real hanky-panky!'”. The gin, vermouth and Fernet Branca Hanky Panky is still served there today.

However the most surprising example of Fernet’s international success isn’t from the bars of London but the students of Argentina. During the late 1800s, Italians emigrating brought with them familiar tastes, drinks and brands. They needed their medicinal Fernet. The company saw the opportunity and licensed local production in Buenos Aires in 1925, still advertising the medicinal properties. In parallel, Coca-Cola was setting up business in Argentina, and becoming more popular throughout the 1940s and 1950s. Smart university students in Córdoba realised that the sweet and cheap Coke mixed well with the bitter, acquired taste of Fernet, making a more accessible and shareable cocktail simply called Fernet con Coca. It took off in that younger, counter-cultural environment. Nowadays, Córdobans drink three million litres of Fernet per year. That’s a staggering 3 litres per adult per year, or 9-10 litres of Fernet and Coke. One of the highest figures for any single spirit anywhere globally. Argentina forms over 75% of Fernet-Branca’s global consumption.

As well as the UK and Argentina, Fernet gained a foothold in the US. During Prohibition (1920-33), alcohol was banned, except for any prescribed for medicinal purposes. This loophole allowed the Italian communities in cities like San Francisco to continue to have their shots of Fernet as a digestive elixir, legally sold via pharmacies. The ongoing availability may have helped the much later growth of Fernet as a niche bartenders’ drink for those in the know, popular in San Franscisco in the 1980s as a bitter “challenge” drink, an after-hours secret, a “bartender’s handshake”, leading to today’s popularity across cocktail and craft beer bars.

Notes on the recipe

As with all self respecting Italian family liqueur brands, the Fernet Branca recipe is a closely guarded secret. However they do reveal it contains 27 herbs, roots and spices, and then tell you about 10 of them on their site. That’s a great start. Of those, you’ll see my recipe has Chinese rhubarb, camomile, cinnamon, linden, iris (orris root), saffron and myrrh. I’ve substituted ginger for galangal. “China” is cinchona, containing quinine (the active ingredient in tonic water), which is one substance I’m a bit scared of. It can cause cinchonism (with symptoms like dizziness, ringing in the ears, blurred vision) or heart issues at more toxic higher doses. So I’ve left that out, as it is hard to know whether you’re within safe limits (and many DIY tonic recipes aren’t). Finally, I couldn’t source zedoary (also called white turmeric). But I am hoping the ginger is a close enough relative.

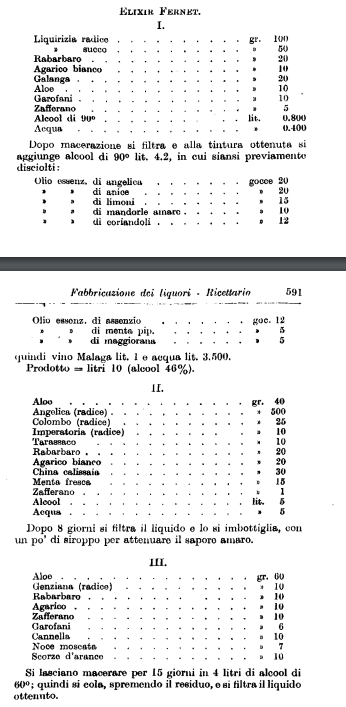

Having exhausted the Fernet Branca web site, we can turn to ancient texts for more clues. Most commonly cited is the famous Il Liquorista Pratico (known to aficionados on Reddit’s r/amaro as simply “ILP”). This comprehensive 442-page liqueur-making manual by the chemist-liquorist Luigi Scala of Milan was published in 1897, with recipes for bitters, amari and assorted elixirs. He included three fernet recipes (I, II and III shown in the image). There’s ingredients in common with the Fernet Branca site, like rhubarb (rabarbaro), saffron (zafferano), mint (menta), cinnamon (cannela). But there’s also liquorice (liquirizia), cloves (garofani), angelica, wormwood (assenzio), gentian (genziana), orange peel (scorze d’arancio) that I’ve included in my recipe. The recipes include “aloe” that is likely the dried, bitter resin from the Cape Aloe succulent plant (Aloe Ferox). I didn’t include that, but will try it next time, as I think that is what will give the black colour as well as add a further bitter, medicinal edge (although I’d suggest small quantities, as it is also a laxative!).

Based on those readings, in this recipe I’ve selected a blend of wormwood and gentian as the primary bitter ingredients, with added angelica and cherry bark.

Fernet Branca has quite a pronounced mint taste. I found this hard to replicate even using a large bunch of mint leaves in the sugar syrup. Possibly I could have added them to the initial infusion, but I’ve never done that with fresh herbs. What I did instead is buy some mint essence and add it at the end (indeed serious amaro makers will generally infuse each ingredient separately so they can more easily balance flavours). This has a very intense taste, but you can easily put less.

I use a very strong neutral alcohol for the main infusion, that extracts flavours much better than something like vodka (although that might work if you left it for longer).

Health benefits of Fernet

Like many tonics and digestifs developed in the 1800s, Fernet came with an impressive array of health claims, “recommended by doctors and pharmacists”. Stimulating digestion, “strengthening” the stomach, reducing nausea and vomiting, expelling internal parasites, increasing energy levels, easing headaches. Unfortunately, by today’s standards, there’s little evidence for any of this. Oft-repeated tales of Fernet being supplied to hospitals in Milan as a cure for Cholera haven’t been verified (and it isn’t a cure!). As Camper English writes in Do Digestifs Actually Work?, “from a strictly scientific standpoint, drinking digestifs as a digestif aid is more fiction than fact.” Enjoy it for what it is.

Damson Fernet recipe

I was pleased with how this came out: strong, bitter, complex, medicinal and with a powerful hit of mint that somehow doesn’t conflict with the fruitiness of the damsons. See what you think!

Damson Fernet

300

mlMake your own strong fernet-style damson amaro in the style of Fernet-Branca, with a bitter, mentholated edge.

Ingredients

- Infusion

All ingredients used for the infusion are in dried form

¼ tsp juniper berries

¼ tsp black walnut hulls

¼ tsp liquorice root

1 tsp bitter orange peel

4 cloves

¼ tsp cherry bark

¼ tsp gentian

¼ tsp myrrh grains

¼ tsp Chinese rhubarb

1 tsp linden leaves and blossoms (sold as linden tea)

¼ tsp orris root

½ tsp ginger

Small piece cinnamon (I used cassia bark)

Pinch saffron

¼ tsp angelica

¼ tsp wormwood

1 tsp camomile

175 ml 70% neutral grain alcohol

- Syrup

100 g demerara sugar

125 ml water

3 bay leaves

1 sprig rosemary

1 bunch mint leaves

- Final maceration

125 g damsons

½ tsp toasted oak chips

2.5 ml mint essence / oil

Directions

- Add all the “infusion” botanicals, herbs and spices to the pure grain alcohol in something like a sealed glass jar, shake and then leave well alone somewhere cool and dark for a week. As the flavours are extracted by the strong alcohol, it will turn an unappealing brown colour.

- A week later, strain the alcohol and keep it, discarding the solids

- Next, make the syrup. Gently heat the water and sugar and stir until the sugar is completely dissolved (no more sugar crystals visible on a spoon or as you stir). Add all the other syrup ingredients, stir and leave to cool, then refrigerate. You can do this ahead and leave it in the fridge for a week, but you need at least a few hours of steeping for the flavours to meld.

- Mix the cooled syrup and the strained alcohol.

- Add the damsons, oak chips and the mint essence.

- Leave in a jar in a cool dark place for a few months (I left mine for 3 months).

- Strain the damsons and oak chips out, and then filter through a coffee filter or fine muslin / cheesecloth into nice bottles. This is quite a small quantity (I ended up with not quite two 200ml bottles) so you may need to scale everything up.

Notes

- The recipe uses 5ml teaspoons and 15ml tablespoons.

- I’m using Holy Lama Spice Drops Mint Extract that is made from spearmint (they also have peppermint). I think the strength of the mint will vary considerably depending on the variety and specific product you use.

- The final product should be 35-40% alcohol, which is a bit stronger than my usual amaro recipes, but similar to Fernet-Branca at 39%.